Understanding In-House vs. ETA Movements

A deep dive into watch calibers: the battle between mass-produced reliability and proprietary artistry, and why it changes the price tag.

Feb 13, 2026 - Written by: Brahim amzil

You’re standing at the counter, looking at two dive watches. They look remarkably similar. Both have stainless steel cases, sapphire crystals, and 300 meters of water resistance. But when you flip the price tags over, your eyebrows hit your hairline.

One is $1,500. The other is $8,500.

The sales associate smiles that knowing smile and whispers a single phrase as if it’s the secret password to an underground society: “This one has an in-house movement.”

If you’re new to the world of horology, this distinction can feel like smoke and mirrors. Is the expensive engine really better, or are you just paying for the branding rights? It’s the single most polarizing topic in modern watch collecting. It divides enthusiasts into two camps: the pragmatists who value reliability and low service costs, and the purists who chase engineering pedigree and exclusivity.

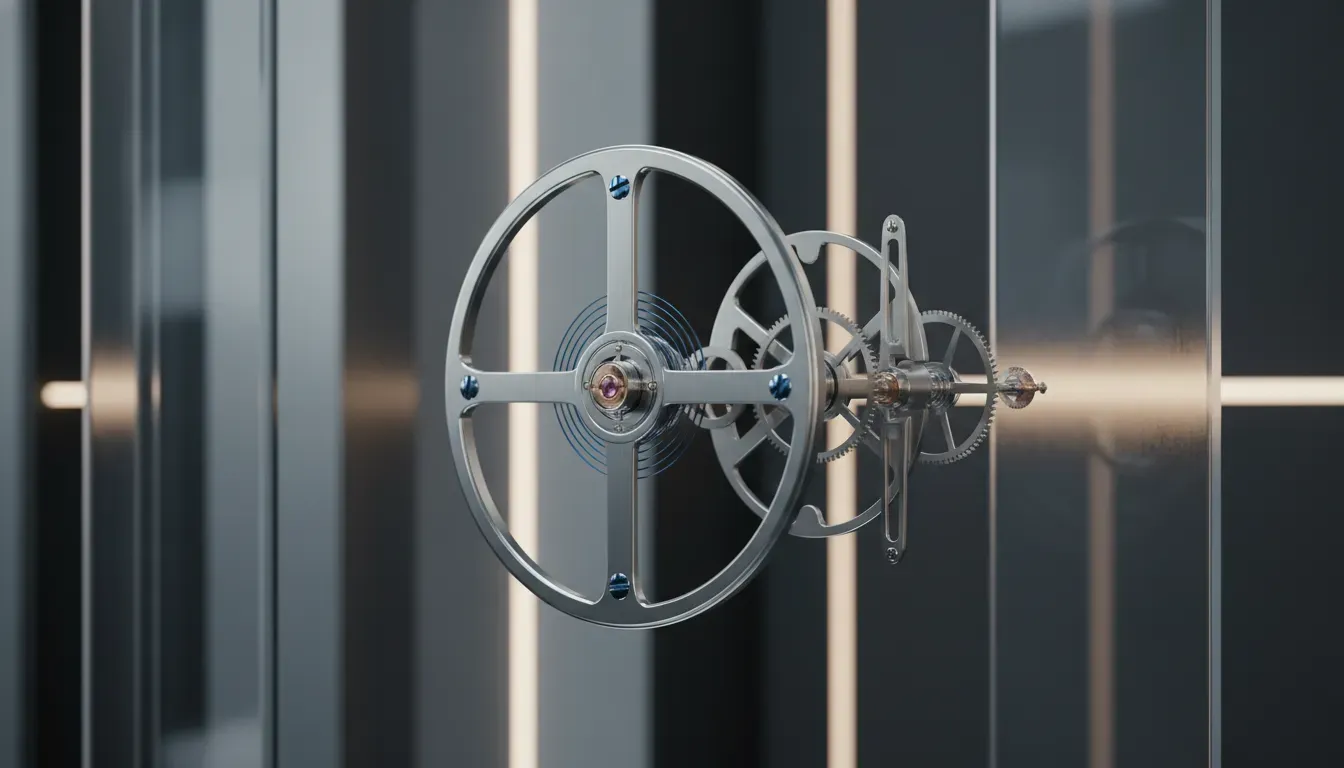

To understand where your money goes, we have to pop the hood. We need to look past the dial and hands to the ticking heart of the machine. This is the battle of the calibers: the ubiquity of ETA versus the prestige of In-House.

The Workhorse: What is an ETA Movement?

Let’s start with the giant in the room. ETA SA Manufacture Horlogère Suisse (ETA for short) is the 800-pound gorilla of the Swiss watch industry. Owned by the Swatch Group, ETA produces millions of movements every year.

Think of an ETA movement—like the legendary 2824-2 or the Valjoux 7750 chronograph—as the horological equivalent of a Toyota engine. It might not look like much through a sapphire caseback (unless heavily decorated), but it is bulletproof. It starts every time. It runs forever. And if it breaks, any mechanic from New York to Nepal has the parts and the know-how to fix it.

The Benefits of Mass Production

For decades, brands that couldn’t afford to build their own factories simply bought engines from ETA. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact, for the consumer, it offers massive advantages:

- Reliability: These designs have been refined over fifty years. The bugs were worked out before most of us were born.

- Serviceability: You don’t need to send the watch back to Switzerland for six months. Your local watchmaker can service an ETA 2824 in their sleep.

- Cost: Because they are produced at scale, they keep the retail price of the watch down.

However, ubiquity kills romance. When you buy a luxury item, you want to feel special. Knowing that your $4,000 IWC Pilot has the same base engine as a $500 Hamilton can be a tough pill to swallow for some collectors.

The Artist: What is an In-House Movement?

“In-house” (or manufacture) implies that the watch brand designed, developed, and assembled the movement entirely within their own facilities. They didn’t buy the engine; they built it from scratch.

This is the realm of Rolex, Patek Philippe, A. Lange & Söhne, and increasingly, brands like Tudor and Omega.

Why does this matter? Vertical integration. When a brand controls every gear, spring, and screw, they have total freedom. They aren’t constrained by the dimensions of an off-the-shelf ETA kit. If they want to move the date window, thin down the profile, or increase the power reserve to 70 hours, they can just do it.

The Price of Exclusivity

Developing a new caliber isn’t like sketching a new dial. It requires millions of dollars in R&D, specialized tooling, and years of prototyping. When you buy a watch with an in-house movement, you are paying for that engineering debt. You are paying for the intellectual property.

But you’re also paying for the “soul” of the watch.

There is a distinct pleasure in knowing that the mechanism on your wrist is unique to that specific brand. It creates a cohesive lineage. The case, the dial, and the movement were all born from the same philosophy.

For those looking to inspect their movements closely, a quality loupe is non-negotiable. Bergeon Watchmakers Loupe 4x

The Grey Area: “Modified” Movements

Here is where things get murky. For a long time, luxury brands would buy raw ETA movements (called ébauches) and modify them. They might replace the mainspring, polish the bridges, or swap out the escapement for higher-grade components.

Is this in-house? No. Is it just a stock ETA? Also no.

Brands like Breitling and IWC were masters of this for years. They took a tractor engine and tuned it up to Formula 1 standards. While purists used to scoff at this, a heavily modified ETA is often more accurate and reliable than a poorly designed in-house caliber. Never assume “In-House” automatically equals “Better Performance.” There are plenty of boutique in-house movements that are fragile, inaccurate, and a nightmare to service.

Why The Industry Shifted

Around the early 2000s, the Swatch Group (owner of ETA) dropped a bombshell. They announced they would slowly stop selling raw movements to brands outside their group. This was the “ETA freeze.”

Panic ensued. Brands that had relied on cheap ETA engines for decades were suddenly staring down the barrel of a supply shortage. They had two choices:

- Buy clones from other suppliers like Sellita.

- Start making their own movements.

This forced innovation. It pushed brands like Tudor, Panerai, and Breitling to invest in their own manufacturing. We are currently living in a golden age of movement variety because brands were forced to sink or swim.

The Pros and Cons: A Cheatsheet

If you are wavering between two timepieces, use this breakdown to check your priorities.

The Case for ETA (and Sellita)

- Lower Entry Price: You get a great watch for under $2,000 usually.

- Cheap Maintenance: A full service might cost $200–$300 locally.

- Thinner Cases: The ETA 2892 is incredibly thin, allowing for sleek dress watches.

- Proven Track Record: It won’t fail you.

The Case for In-House

- Prestige & Resale: Collectors value propriety. These watches generally hold value better (brand dependent).

- Specs: Often feature better specs like 70+ hour power reserves, silicon hairsprings, and anti-magnetic properties.

- Beauty: Generally speaking, in-house movements have superior finishing (Geneva stripes, perlage, chamfered edges).

- Bragging Rights: Let’s be honest, it feels good to know.

However, be warned: servicing an in-house movement is costly. You are trapped in the brand’s ecosystem. A service on a sophisticated in-house chronograph can easily run $800 to $1,500 and take months to complete.

To keep your automatic watches running when you aren’t wearing them—especially those with complicated in-house calendar functions—a winder is essential. Wolf Heritage Single Watch Winder

Visual Cues: How to Spot the Difference

You don’t always need to open the caseback to know what’s going on.

The Power Reserve: Standard ETA movements typically have a power reserve of around 38 to 42 hours. If a watch boasts a 70-hour or 3-day power reserve (like the Tudor Black Bay or new Oris Calibre 400), it’s almost certainly an in-house or proprietary movement.

The Date Window: ETA movements have fixed architecture. The date wheel is where it is. If you see a large watch (44mm) and the date window seems uncomfortably close to the center of the dial, that’s a tell-tale sign of a small ETA movement inside a large case. In-house movements are often sized perfectly to the case, allowing the date to sit properly at the edge.

The Noise: The Valjoux 7750 (a common chronograph movement) has a famous “wobble.” The rotor only winds in one direction and spins freely in the other. If you flick your wrist and feel the watch vibrating like a living thing, you’re likely wearing a 7750.

The Rise of “Kenissi” and Collaborative Manufacturing

The binary distinction of “In-House vs. Outsourced” is dissolving. We are seeing a new trend: the manufacturing collective.

Kenissi is a movement manufacturer founded by Tudor. But they don’t just supply Tudor. They now produce movements for Breitling, Chanel, and Norqain. These aren’t generic off-the-shelf engines; they are high-spec, industrial movements built to shared standards.

Is it in-house? Sort of. It’s “Group-House.” This is the future of the mid-tier luxury market—sharing the massive cost of R&D across multiple brands to produce a superior engine that rivals Rolex for performance, without the $10,000 price tag.

If you are starting to collect, you’ll eventually need the right tools to swap straps or adjust bracelets, regardless of the movement inside. Bergeon 7767-F Watch Spring Bar Tool

The Verdict: Which One Should You Buy?

Here is the truth that snobs hate to admit: A watch is not better simply because the movement is in-house.

A standard ETA 2824 regulated to COSC (chronometer) standards will keep time just as well as a Patek Philippe. The difference is not utility; the difference is art.

If you are buying a watch to wear while mowing the lawn, hiking, or banging against door frames, an ETA or Sellita movement is a smart choice. It’s robust, replaceable, and cheap to fix. It’s the pickup truck of the watch world.

But if you are buying a watch to celebrate a milestone, to pass down to your children, or to marvel at the microscopic city of gears working in harmony, the premium for an in-house caliber is justified. You are buying a piece of mechanical history, a machine that was dreamed up and brought to life by a single house.

Understanding the “Tax” of Luxury

Ultimately, the “In-House Tax” is a tax on romance. It’s the price you pay for the story.

When you look at Vintage Watches, you’ll see that collectors obsess over caliber numbers. A “Caliber 321” Speedmaster commands thousands more than a “Caliber 861” simply because of the construction and history of the gears.

Don’t let the specs sheet dictate your emotions. If you love the design of a watch, buy it. It doesn’t matter if the engine came from a mass-production line or a hermetically sealed cleanroom in Le Sentier. The best movement is the one that keeps ticking on your wrist while you live your life.

But now, at least when that sales associate whispers about “proprietary engineering,” you’ll know exactly what you’re paying for—and whether it’s worth it to you.